What is the Pelvic Floor?

An Anatomy Series on the Pelvic Floor:

The Levator Ani Muscles and an Introduction to Muscle Tension

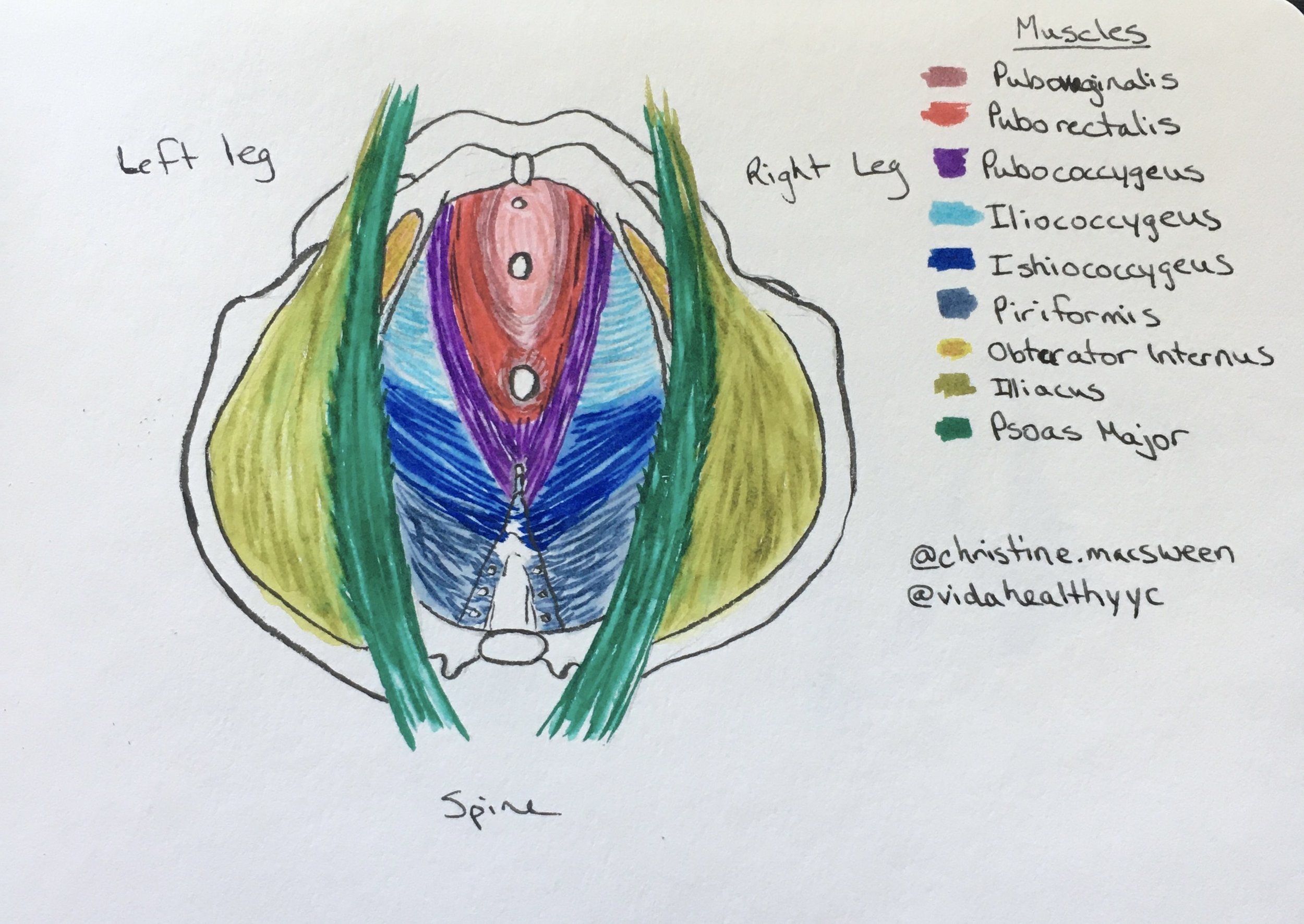

Watercolor diagram of the anatomy of the pelvic floor (aka pelvic diaphragm).

Let’s start this series here, at the pelvic diaphragm (pelvic floor). I prefer the name diaphragm because it is a much better description of its function.

It’s not a floor that we want to be hard. It is more like a trampoline, and if you are one of my patients, you might be familiar with the visualization of the trampoline and the springs. We want these tissues to be reflexive, responsive and mobile. We want it to move with our breath and be able to respond to the activities we do in our daily lives.

The Nitty Gritty Anatomy

The pubococcygeus muscle group (aka the Levator Ani Muscles) generally acts as what I call our “squeezer” muscles. They assist our sphincters (urethral and anal) in keeping things in (pee and poop), and ideally, they relax when we need to get these things out.

In this group, we have three muscles:

Pubovaginalis: for women and those with vaginal canals, this is a muscle that loops from the pubic bone around the vagina. The more I work with patients with vaginismus (a condition where the muscles around the vagina do not allow for penetration), the more I think of this muscle as a sphincter for the vagina. When it’s overactive, it can make sex painful, and even make it difficult to insert a tampon or anything else.

Puborectalis: this muscle loops around the rectum and actually creates a kink in the rectum to help keep stool in. When this muscle is overactive, it can also contribute to painful sex, along with constipation.

Pubococcygeus: this one attaches from the inside of the pubic bone and goes all the way to the tailbone. When it’s contracting, I tend to think of it as doors that try to squeeze shut - like sliding doors. It can also create a bit of a lift, but there are other muscles in the pelvic floor that do more of the lifting. It can also tuck your tailbone. When it lengthens, the tailbone moves away from the pubic bone.

These are only 3 of the muscles of the pelvic diaphragm, and I will be expanding on the others soon.

Muscle tension lives on a spectrum

Why am I talking about overactivity so much? Because that is the majority of what I see in clinic. Certainly not all cases, but I would hazard a guess at 80% or more of my pelvic health caseload.

What does overactive even mean? The lay person’s terms would be that these muscles are too tight or too tense. They may also be painful. Did you know you can leak pee even if the muscles are too tight?

But truly, muscle tension lives on a spectrum. Tension itself is not a bad thing, and is an important part of how muscles function. We require tension to move. Muscles with not enough tension, will usually be classed as weak, but muscles with too much tension can also be weak. The questions become, what is the capacity of this muscle, can it move through its intended range of motion, and can do these things with the appropriate timing/coordination? For all muscles, this means having the ability to shorten, lengthen, and relax in response to the task at hand.

In the case of the pelvic floor, an example is being able to lengthen in preparation of a sneeze or cough, contract under the pressure, and then relax afterwards - all without allowing urine to leak. This includes not having to cross the legs!

There is so much more we can talk about such as what causes muscle tension, and what to do for muscle tension, but we will save those for a future post. We will also cover more of the pelvic floor muscles!

Did you learn anything new? Do you see yourself in any of these explanations and are ready to get assessed? Look for a local pelvic floor therapist near you, and if you are in Calgary, AB, you are welcome to come see me!

This post was originally published on Vida Health & Wellness .